In order to better understand medial collateral ligament (MCL) and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injuries, it is important to understand basic knee anatomy and the function of the MCL and the LCL. Please review the section on knee anatomy before reading this section.

Where are the medial and lateral collateral ligaments of the knee?

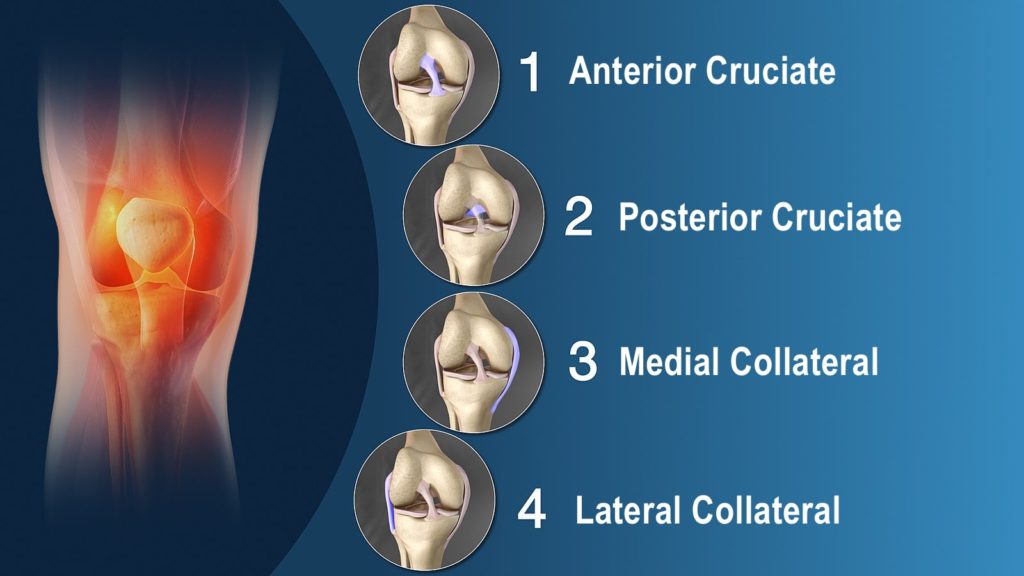

Ligaments are like strong ropes that help connect bones together and provide stability to joints. In the knee, there are four main ligaments. On the inner (medial) aspect of the knee is the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and on the outer (lateral) aspect of the knee is the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). The other two main ligaments are found in the center of the knee. These paired ligaments are called the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). They are called cruciate ligaments because the ACL “crosses” in front of the PCL.

What is the function of the collateral ligaments of the knee?

The MCL and the LCL work together with ACL and the PCL to keep the knee joint stable during movement. The MCL and LCL provide support at the inner and outer aspects of the knee while the ACL and the PCL lend support at the center of the knee. Tears of the MCL or LCL may be mild (grade I), moderate (grade II) or severe (grade III). MCL and LCL injuries differ from ACL and PCL injuries in that mild to moderate tears have the ability to heal following injury. Grade III injuries to the MCL or LCL are more serious and are often associated with other knee injuries.

How do the collateral ligaments get injured?

The MCL is usually injured by a “blow” to the outer side of the leg (valgus force). A “blow” to the inner side of the leg (varus force) may injure the LCL. MCL injuries are far more common than LCL injuries and are often seen in contact sports. At the time of the injury there is often immediate pain and sometimes swelling can occur. A “pop” or “snap” may be felt or heard and the knee may feel “unstable” during certain movements.

As mentioned previously MCL or LCL injuries can vary in severity. Tears may be partial (grades I and II) or complete (grade III). Larger tears result in greater instability of the knee joint. Injuries to other structures inside the knee can occur when either the MCL or LCL are injured. The cartilage (menisci) inside the knee can be injured as can the ACL or PCL (the cruciate ligaments). Injuries to other structures are more likely if there was a significant force or if there was a rotational component at the time of injury. A bone injury or fracture can occur, particularly, in young growing athletes.

How do you detect collateral ligament injuries?

Examination techniques that detect side to side (valgus-varus) looseness in the knee are effective in detecting collateral ligament tears. Tests that detect forward-backward (anterior-posterior) or rotational looseness can help detect other ligament injuries. X-rays are often done at the time of injury to make sure the bones of the knee are not broken. Tests such as Magnetic Resonance Images (MRI) are rarely required for collateral ligament injuries but are occasionally used to rule out other injuries to the knee.

What is the treatment for collateral ligament injuries?

The treatment of MCL and LCL injuries depends on the severity of the injury and other associated injuries. Each treatment plan should be individualized. Initially, protection (by use of crutches and/or a rehabilitation brace), rest, ice, compression and elevation (PRICE) of the injury will help reduce pain and/or swelling.

After an MCL or LCL injury, the long term goal is to return the individual back to their previous level of activity. A general knee rehabilitation program which includes strengthening exercises, flexibility exercises, aerobic conditioning, technique refinement and proprioceptive (biofeedback) retraining is the most important factor in achieving this goal. Some people with MCL or LCL injuries report an improved sense of stability when wearing a collateral ligament brace.

Even with the most ideal treatment the knee may never be as “normal” as the uninjured knee and modification of activity may be required. However, doctors and physiotherapists trained in treating MCL and LCL injuries can outline an individualized treatment plan which will maximize the long-term function and stability of the knee.

To read more about collateral ligament braces click here. Please visit the links section for additional information on MCL and LCL injuries. Links have been provided to other websites as well as online medical journals. Other knee injury topics can also be accessed.